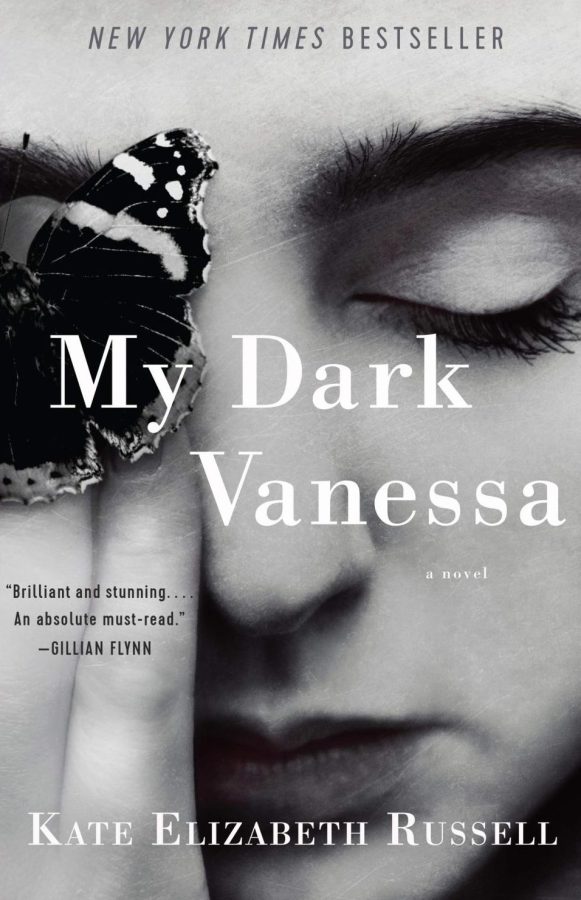

My Dark Vanessa: A Re-Evaluation of the Age Gap Romance Trope

April 5, 2022

Adult Vanessa, an overworked hotel concierge, has spent her entire life disguising, eliminating, and replaying what has happened over and over. She still has Strane, her abuser and high school English teacher, feeding her false information, deluding her, and providing her with more information to help her rewrite the events that happened to her 15-year-old self for the past 20 years. “Even if I sometimes use the word abuse to describe certain things that were done to me, in someone else’s mouth the word turns ugly and absolute. It swallows up everything that happened. It swallows me and all the times I wanted it, begged for it,” Vanessa muses.

Kate Elizabeth Russell’s uncomfortable yet brilliant debut novel, My Dark Vanessa, explores this topic, becoming a minefield in which language is open to be interpreted in numerous ways. With our current society, in the wake of the #MeToo movement, there have been floods of articles and novels that reconsider the meaning behind the Lolita story, amending the theme of Vladimir Nabokov’s original. These readjustments not only reveal the other side of the Lolita narrative, but also the tragic and forgotten real-life tale of Sally Horner, who’s abduction and murder Nabokov alludes to. My Dark Vanessa adds to this reevaluation: an example of the story told from the girl’s point of view, rather than the inherent justification of the man’s.

Altering between two timelines, one of the past and one of the present, the novel depicts the life of Vanessa Wye, a 15-year-old adolescent longing for the sensation of adulthood, and 42-year-old Jacob Strane, her abuser and English teacher. Taking place at an elite boarding school in Maine, My Dark Vanessa unpacks the affair – but most importantly the abuse that took place between Vanessa and Strane, foregrounding her reluctance to recognize Strane’s behavior for what it was 17 years later.

Strane exploits Vanessa’s moral grayness as a way to insert himself into her life. He offers her literature and poetry that reflect her maple-leaf colored hair and bookish persona, such as Sylvia Plath’s “Ariel”, (“Out of the ash, I rise with my red hair/And I eat men like air”), but most obviously, his annotated copy of Nabokov’s Lolita, which remains the distorted common ground in their unhinged relationship. Allowing her to believe these novels are forbidden love stories, he maneuvers this as an entrance into her life, imposing his own demonic presence onto her. The title is derived from Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov, from which Strane feeds Vanessa the line, “Come and be worshiped, come and be caressed, my dark Vanessa.”

Early on in the novel, readers can recognize Vanessa as the typical unreliable narrator. She misunderstands her own experiences with sexual abuse, in which she’s engulfed by Strane’s overbearing nature. Strane’s manipulation stems from this false hope to protect Vanessa’s innocence: to keep her a child, and in doing so he warps Vanessa’s vulnerability and view of herself. She says: “This, I think, is what it means to be selfless, to be good. How could I ever have thought of myself as helpless when I alone have the power to save him?”

But if there’s one thing that Fiona Apple loving teenage Vanessa is absolutely correct about, it was that she is normal. Enthralled by literature and the possibility of making someone fall in love with her, she craved this feeling of needing desire, of maturity. To the reader, it’s disturbingly obvious that Strane sees Vanessa as a child, which is primarily why he is so fascinated with her. Vanessa’s disillusionment and ultimate discontent with reality transform into this romanticization and her need for human protection.

The language in this novel is very self referential, containing ciphered words needing to be decoded by the audience in the same way Nabokov uses elaborate language to manipulate trust in the audience. We see bursts of certainty when Vanessa can finally see through her own blindness and her dialect reflects reality, as she illustrates: “I feel forced over a threshold, thrust out of my ordinary life into a place where it’s possible for grown men to be so pathetically in love with me they fall at my feet.” Yet this clarity is decimated as Vanessa tries to delude herself. Vanessa manages to escape closure from her past time and time again, protecting herself from reality, as the idea of being in love is not something she wants, but something she needs.

This book is suspenseful, hooking its readers with the explicit double timeline. Russell is able to capture the essence of a mystery–being left with so little at the end of each chapter develops this hunger to know and understand more. Russell’s novel entertains reader interpretation by leaving this purposeful nuanced gray area within all the characters. Vanessa’s troubled background and isolation from her parents enables us to understand and sympathize with her turmoil. With each layer of her character peeled back, there is another one even more complex than the next.

Language is used as a twisted barrier between the reader and Vanessa. It is also one of the compulsions shared between Strane and Vanessa– he perverts it, she fears it. At one point in the novel, Vanessa’s conception of reality is so oblique that when talking to her college professor, she mistakes her experience for Lolita’s. She internalizes a scene where Humbert buys Lolita strawberry pajamas to wear to bed, when in actuality it was Strane who had given them to her.

Sporadically, the writing may toggle from ponderous to convoluted to seemingly paradoxical, as Russell tends to overanalyze as a way to maintain the ambiguities of the characters in the future. Nonetheless, this novel transforms seemingly insignificant details into a cleverly unsettling commentary on the human race.

Whether or not My Dark Vanessa is the contemporary Lolita, Russell explores the themes of victimhood, trauma, abuse, misplacing power and consent. She critiques the society we live in today, by showing the demoralizing experiences so many sexual assault survivors go through. How society grants them a fear of the repercussions from their abusers, rather than safety. She ultimately explains the condition of victimhood: not being heard, seen, nor believed– illustrating how the search for security can be everlasting as humankind has yet to evolve out of victim-blaming and retaliation.

It’s difficult to create a brutally daring and fresh novel, but Russell manages to spin an intricate web of lies and manipulation. My Dark Vanessa is far from a forbidden love story; it encompasses the zeitgeist of the early 2000s, as well as the present day, laying the foundation for a reassessment of the unhealthy age-gap romance trope.

Human nature shows we’d do anything to protect ourselves from pain: we put up walls in our own brains, we lie to ourselves, and rather than facing the truth, we manipulate memories into something we can handle.

Scarlett Kennedy • Apr 7, 2022 at 10:35 am

Your writing is so in depth and interesting to read, I feel enlightened